Art on Its Own Terms: Author Amelia Peck on Gee's Bend Quilts in My Soul Has Grown Deep

My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South,

by Cheryl Finley, Randall R. Griffey, Amelia Peck, and Darryl Pinckney,

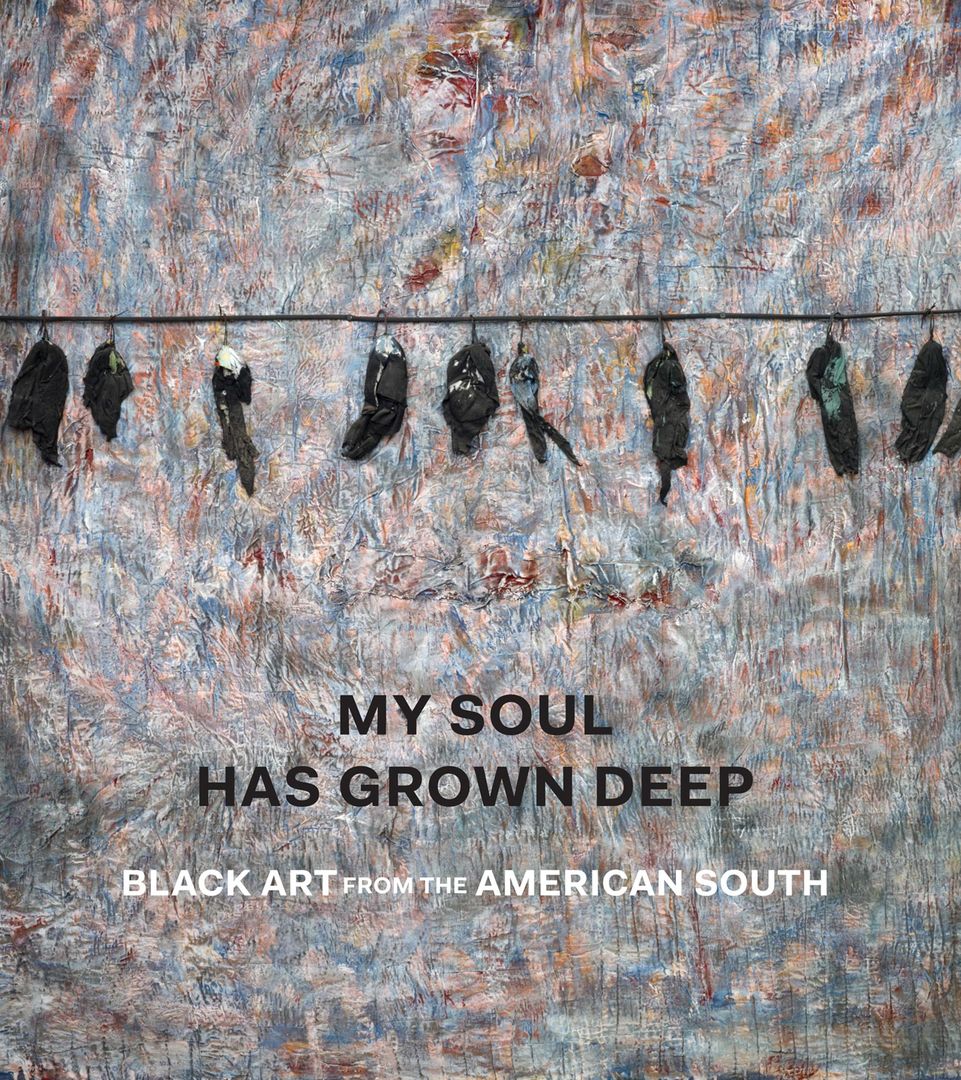

featuring 112 full-color illustrations, is available at The Met Store and MetPublications. Cover: Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly

(detail), 2007. Quilt, wire, fabric, and enamel on canvas on wood, 72 x

72 in. (182.9 x 182.9 cm). Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the

William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.5). © Thornton Dial

Recently published by The Met, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South accompanies the exhibition History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation,

on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 23. The show and the

catalogue consider the art-historical significance of contemporary black

artists working in the southeastern United States, particularly those

working around greater Birmingham, Alabama.

The paintings, drawings, mixed-media compositions, sculptures, and textiles included in the book range from the profound assemblages of Thornton Dial to the renowned quilts produced in Gee's Bend, Alabama. In a departure from earlier scholarship, this remarkable study considers these works on their own merits, while also telling the compelling stories of artists who overcame enormous obstacles to create distinctive and culturally resonant works of art.

In a recent review of the catalogue, the Wall Street Journal praised Amelia Peck's essay on the Gee's Bend quilters, "Quilt/Art: Deconstructing the Gee's Bend Quilt Phenomenon," in which she questions some of the commonly held assumptions about these works of art. I had the opportunity to speak with Amelia about her essay, American traditions of quilting, and the slippery distinction between art and craft.

The paintings, drawings, mixed-media compositions, sculptures, and textiles included in the book range from the profound assemblages of Thornton Dial to the renowned quilts produced in Gee's Bend, Alabama. In a departure from earlier scholarship, this remarkable study considers these works on their own merits, while also telling the compelling stories of artists who overcame enormous obstacles to create distinctive and culturally resonant works of art.

In a recent review of the catalogue, the Wall Street Journal praised Amelia Peck's essay on the Gee's Bend quilters, "Quilt/Art: Deconstructing the Gee's Bend Quilt Phenomenon," in which she questions some of the commonly held assumptions about these works of art. I had the opportunity to speak with Amelia about her essay, American traditions of quilting, and the slippery distinction between art and craft.

Barnett Newman's Concord and Loretta Pettway's Lazy Gal Bars quilt may share visual similarities, but they come from entirely different traditions. Left: Barnett Newman (American, 1905–1970). Concord,

1949. Oil and masking tape on canvas, 89 3/4 x 53 5/8 in. (228 x 136.2

cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund,

1968 (68.178). © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right:

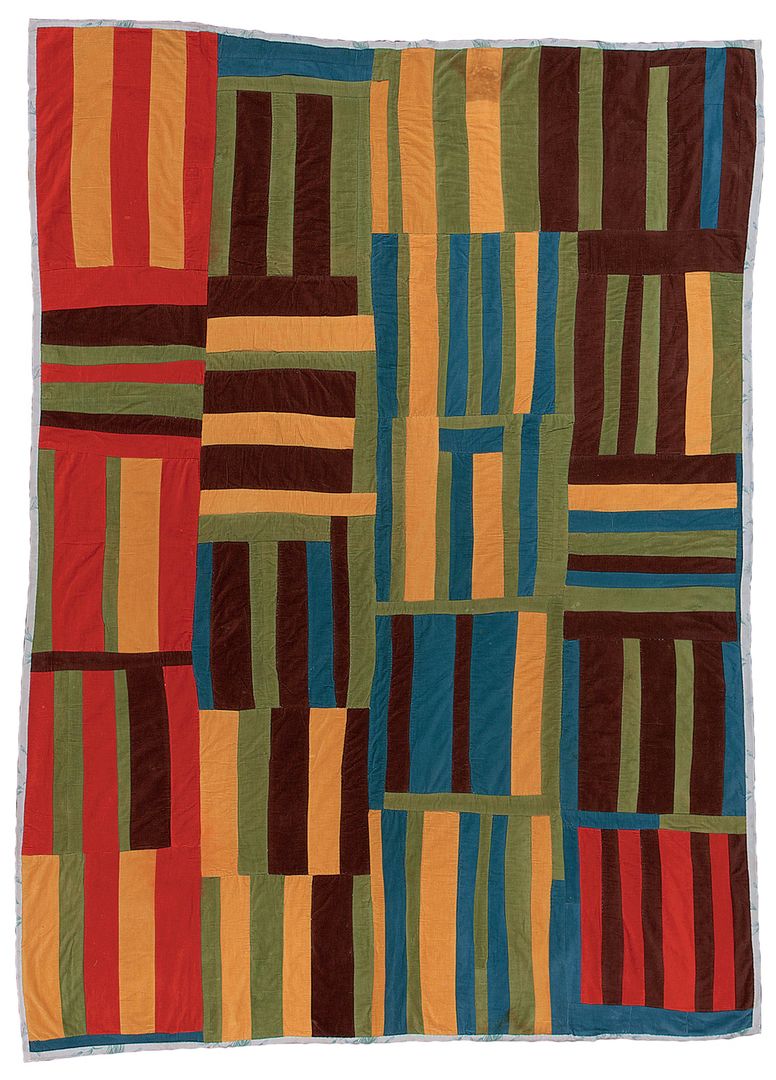

Loretta Pettway, (American, born 1942). Lazy Gal Bars quilt,

ca. 1965. Top: cotton and cotton-polyester blend; back: polyester;

binding: self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 80 1/2 x 68

1/2 in. (204.5 x 174 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift

of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection,

2014 (2014.548.50)

Rachel High: The quilts featured in My Soul Has Grown Deep

first spent time on beds in Gee's Bend before The Met hung them on the

walls of its galleries. Women working outside of traditional art-world

paradigms created these compelling textiles. Both of these facts

traditionally precluded the quilts from being considered as works of

art. In asserting the value of the margin, it is often tempting to

compare it to the center—even if that is actually a superficial

comparison. Previous scholars have compared the Gee's Bend quilts to

abstract paintings. In your essay, you reject this interpretation. Why?

Amelia Peck: To say that they look like abstract paintings is an easy, though superficial, way to understand Gee's Bend quilts. The women making these quilts never saw the abstract paintings that their work supposedly references.

There's a marketplace component to this view; this comparison was an attempt to raise their value—I'm not talking simply about monetary value, but rather the validity of these quilts as works of art. Earlier generations couldn't see them as anything other than domestic. "Women" and "domestic" are uncomfortable categories for most classically trained art critics; a useful object made by women for the home that also happened to be beautiful was not considered art.

For a long time, critics compared graphic quilts to abstract art painted by men as an easy way to make sense of them and to make them into something more valuable than just a bed covering—more of a "real" work of art.

Amelia Peck: To say that they look like abstract paintings is an easy, though superficial, way to understand Gee's Bend quilts. The women making these quilts never saw the abstract paintings that their work supposedly references.

There's a marketplace component to this view; this comparison was an attempt to raise their value—I'm not talking simply about monetary value, but rather the validity of these quilts as works of art. Earlier generations couldn't see them as anything other than domestic. "Women" and "domestic" are uncomfortable categories for most classically trained art critics; a useful object made by women for the home that also happened to be beautiful was not considered art.

For a long time, critics compared graphic quilts to abstract art painted by men as an easy way to make sense of them and to make them into something more valuable than just a bed covering—more of a "real" work of art.

Amish quilts, like the one on the left, were similarly compared to abstract painting, even though the makers had little exposure to these trends in contemporary art. Gee's Bend artists adapted traditional quilting patterns but improvised with the patterns and used materials that were readily available to them, like recycled denim work clothes. Left: Amish maker. Quilt, Split Bars pattern, ca. 1930. Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Wool and cotton, 87 x 77 in. (221 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jan P. Adelson and Joyce B. Cowin Gifts, 2004 (2004.26). Right: Annie Mae Young (American, 1928–2012). Strip Medallion quilt, 1976. Top: cotton and cotton-polyester blend; back: cotton-polyester blend; binding: self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 104 1/2 x 77 in. (265.4 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.57)

Rachel High: Your essay made me realize how

innovative the Gee's Bend quilters are in adapting traditional quilting

patterns. You wrote that the Gee's Bend quilts in The Met collection

reference and blend five traditional patterns, and that "by breaking and

blending patterns, the designs are filled with action and vibrancy."

What is it about the Gee's Bend environment that made their innovations

possible?

Amelia Peck: I think it was a combination of things. These patterns were passed down through generations of Gee's Bend women. Patterns that were typical across the country in the mid-to-late nineteenth century were still being made by Gee's Bend quilters much later, into the twentieth century. That said, these traditional patterns were made less and less traditional over the years by the visual sensibility of the original quilters, who then taught their children and their grandchildren. They put their own particular spin on things. For example, the Gee's Bend quilters often used different materials than those used in more traditional quilts, and they mostly depended upon reused fabrics.

The myth of patchwork quilts has always been that all patchwork quilts are made from leftover scraps collected by women. That is not necessarily the case—in fact, it is usually not the case. In many nineteenth-century quilts, much, if not all, of the fabric was brand new. In the case of the Gee's Bend quilters, however, they really were cutting up old clothes and other readily available fabric, which they didn't have to buy new, to create their quilts. For the corduroy quilts, they used scraps left over from a large commission making cushion covers for Sears, Roebuck and Company in the 1970s. The Freedom Quilting Bee, a collective to which many of the Gee's Bend quilters belonged, organized that work.

Amelia Peck: I think it was a combination of things. These patterns were passed down through generations of Gee's Bend women. Patterns that were typical across the country in the mid-to-late nineteenth century were still being made by Gee's Bend quilters much later, into the twentieth century. That said, these traditional patterns were made less and less traditional over the years by the visual sensibility of the original quilters, who then taught their children and their grandchildren. They put their own particular spin on things. For example, the Gee's Bend quilters often used different materials than those used in more traditional quilts, and they mostly depended upon reused fabrics.

The myth of patchwork quilts has always been that all patchwork quilts are made from leftover scraps collected by women. That is not necessarily the case—in fact, it is usually not the case. In many nineteenth-century quilts, much, if not all, of the fabric was brand new. In the case of the Gee's Bend quilters, however, they really were cutting up old clothes and other readily available fabric, which they didn't have to buy new, to create their quilts. For the corduroy quilts, they used scraps left over from a large commission making cushion covers for Sears, Roebuck and Company in the 1970s. The Freedom Quilting Bee, a collective to which many of the Gee's Bend quilters belonged, organized that work.

Scraps

of corduroy left over from the Sears, Roebuck and Company commission

organized by Freedom Quilting Bee make up this quilt. Willie "Ma Willie"

Abrams (American, 1897–1987). Roman Stripes quilt,

ca. 1975. Top: cotton; back: cotton-polyester blend; binding:

self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 93 1/4 x 70 in. (236.9 x

177.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls

Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett. 2014 (2014.548.38)

There was also an element of necessity in the quilters' innovations. I

read about and talked to some of the women from the Gee's Bend area

when researching for the catalogue; I don't want to generalize too much,

but a lot of the women had very large families and lived in houses

where they really needed to make these quilts to keep their families

warm. The Gee's Bend quilters weren't going to spend a year piecing

together lots of tiny bits of fabric to make an absolutely perfect,

predefined pattern. Instead, they worked pretty quickly and used larger

pieces of fabric if available. They improvised with what they had and

created patterns that were very decorative and attractive but were not

the laborious and overly intricate patterns created in wealthier

communities, where women had more leisure time.

Rachel High: Unlike the objects in the rest of the book by the artists of the Birmingham-Bessemer group, which mostly date from the last fifty years, the Gee's Bend quilts go as far back as the 1930s. How are the quilts in dialogue with the more recent works featured in the publication?

Amelia Peck: Until we started installing the show, I didn't realize how many of Thornton Dial's works incorporated textiles. The work by Dial on the cover of the book, The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly, is actually painted on a quilt. Ronald Lockett's great aunt Sarah Dial Lockett was a famed quilter. The quilts were very much a part of the local art world in the area of Alabama where most of these artists lived. Even though the Gee's Bend quilts have been shown separately from these paintings and sculptures in the past, the male and female artists knew each other's work.

Rachel High: Unlike the objects in the rest of the book by the artists of the Birmingham-Bessemer group, which mostly date from the last fifty years, the Gee's Bend quilts go as far back as the 1930s. How are the quilts in dialogue with the more recent works featured in the publication?

Amelia Peck: Until we started installing the show, I didn't realize how many of Thornton Dial's works incorporated textiles. The work by Dial on the cover of the book, The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly, is actually painted on a quilt. Ronald Lockett's great aunt Sarah Dial Lockett was a famed quilter. The quilts were very much a part of the local art world in the area of Alabama where most of these artists lived. Even though the Gee's Bend quilts have been shown separately from these paintings and sculptures in the past, the male and female artists knew each other's work.

The

quilters and the other artists in the catalogue worked in the same area

and shared ideas. Many of the male artists also used textiles in their

work or were influenced by the aesthetics of quilts. The catalogue's

cover features a painting by Thornton Dial that uses a quilt as its

base. Ronald Lockett's great aunt was a well-known quilter, and his work

shows similar interest in found materials and in the composition of the patterns of local quilts. Left: Ronald Lockett (American, 1965–1998). The Enemy Amongst Us,

1995. Commercial paint, pine needles, metal, and nails on plywood, 50 x

53 x 3 in. (127 x 134.6 x 7.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett

Collection, 2014 (2014.548.10)

Rachel High: At the end of the essay, you discuss the difference between art and craft. What do both words mean to you? Are they mutually exclusive?

Amelia Peck: As a textile curator who has spent a lot of time studying and exhibiting women's work, I came to the conclusion in my essay that there is no difference, in my mind, between art and craft. Of course, there is textile art, which contemporary artists are making today with the intention that the finished product will hang in a museum, but throughout history, women were making very fine textiles that were intended to highlight their artistic talents, even if they weren't shown outside the home.

The women of Gee's Bend describe creating the quilts as a process of finding combinations of colors and patterns that pleased their eyes. My conclusion is that these quilts are art because the women of Gee's Bend had an intentional vision: they were composing artworks by putting pieces of various fabrics together, no differently than the other artists in the show would compose a painting or an assemblage.

No comments:

Post a Comment