Another shot from our yard, this one of some of the dahlias that get more sun so have many more blossoms than the others, and the daisies (I think) and the clematis that grow near them.

Remember, you can click on the image to see a bigger version. The full-resolution one is on Flickr.

Sunday, August 26, 2018

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Late-summer

I often send along photos of the front walk covered in snow. Thought I'd switch things up & show you what it looks like late-summer, thanks to Andy's tender gardening. Remember you can see a larger version by clicking on the picture.

We're lucky we're not in CA or Hawaii. Time will tell what Mother Nature has in store for us.

We're lucky we're not in CA or Hawaii. Time will tell what Mother Nature has in store for us.

Saturday, August 18, 2018

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Monday, August 13, 2018

Eternal Springtime

Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet from the Burrell Collection

July 10, 2018

Sheila Canby, Patti Cadby Birch Curator in Charge, Department of Islamic Art

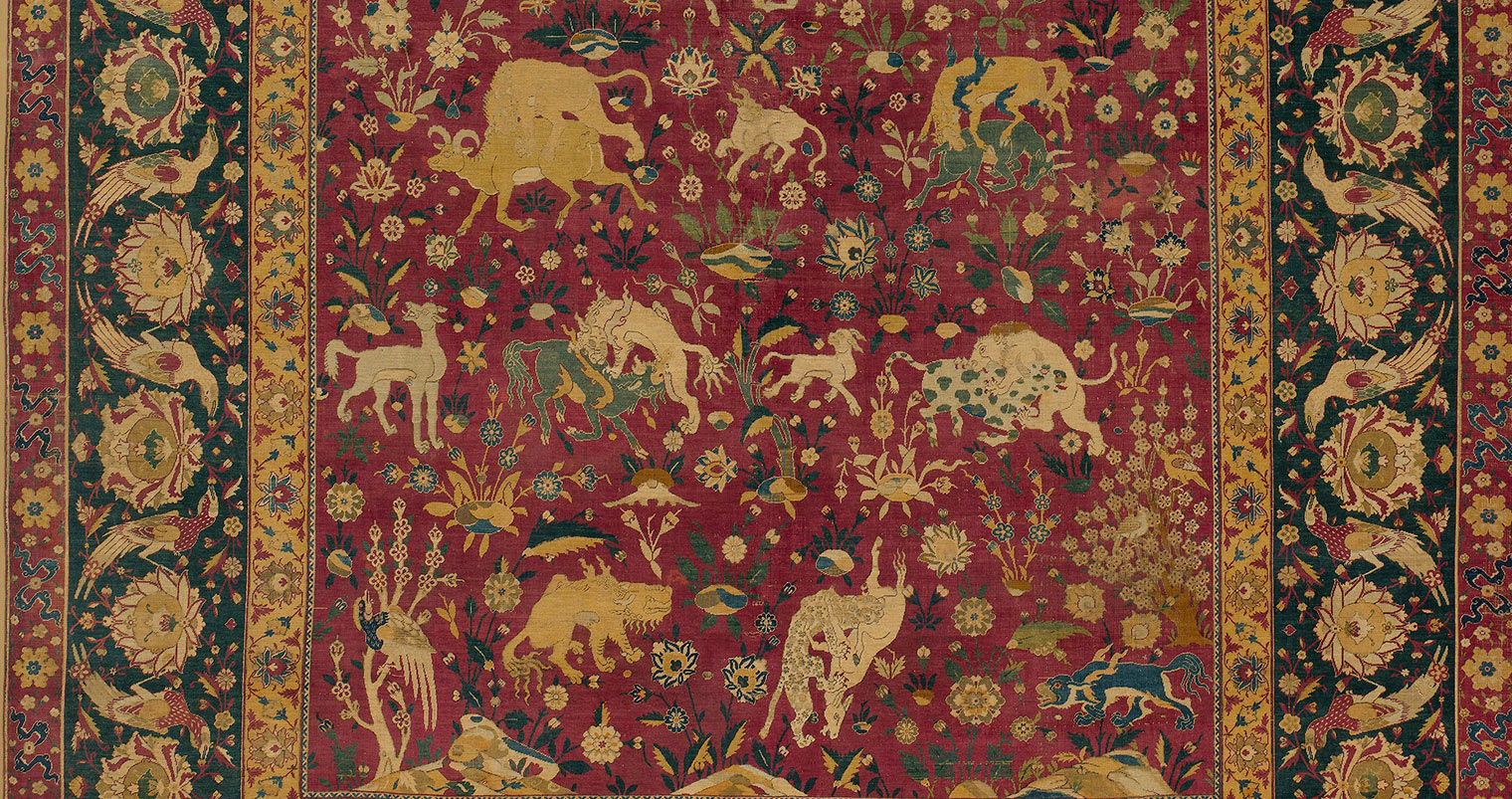

From July to October, regardless of the weather outside, visitors will be able to enjoy springtime, embodied in a grand Persian garden carpet on loan from the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, Scotland. Called the "Wagner Garden Carpet" after a former owner, this carpet will be on view in an American museum for the first time. It is the third-oldest-known Persian garden carpet, dating from the seventeenth century, whereas the three later examples in The Met collection were produced in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The weaving technique of the carpet supports an attribution to Kirman in southeastern Iran, while the later examples are considered products of Kurdistan in western Iran.

Sheila Canby, Patti Cadby Birch Curator in Charge, Department of Islamic Art

From July to October, regardless of the weather outside, visitors will be able to enjoy springtime, embodied in a grand Persian garden carpet on loan from the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, Scotland. Called the "Wagner Garden Carpet" after a former owner, this carpet will be on view in an American museum for the first time. It is the third-oldest-known Persian garden carpet, dating from the seventeenth century, whereas the three later examples in The Met collection were produced in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The weaving technique of the carpet supports an attribution to Kirman in southeastern Iran, while the later examples are considered products of Kurdistan in western Iran.

The

"Wagner" Garden Carpet, 17th century. Iran, Kirman. Cotton warp; wool,

cotton, and silk weft; wool pile. Lent by Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums)

on behalf of Glasgow City Council: from the Burrell Collection with the

approval of the Burrell Trustees. On view in gallery 462

What makes the Wagner Garden Carpet so special? Similar to the other

two seventeenth-century garden carpets, this one contains a dizzying

array of birds, animals, insects, fish, and even snails amidst flowers

and leafy trees. It buzzes with life. Humorous or dangerous encounters

between animals take place in a formal setting based on the classic chahar bagh (literally,

"four garden") plan of Persian gardens. However, the Wagner carpet does

not follow the standard plan with a vertical central water channel

intersected by a large horizontal channel to form four rectangles

planted with trees and flowers. Instead, two channels run the length of

the carpet and are joined by a horizontal channel that does not extend

to the lateral edges of the rug. At the point of intersection is a

stepped rectangle, which is a repaired area that may have originally

contained a pavilion.

Lower half of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

Although all gardens change over time, the walled garden with water

channels maintained its popularity in Iran well into the twentieth

century. As in the lower half of the Wagner carpet (above), channels

were lined with cypress and chinar, or plane trees, a variety

of the sycamore. These trees provided shade and color contrast. In the

hot, arid Iranian climate, water is scarce, transported to towns and

cities by underground canals that capture snowmelt from the mountains

and move it great distances. Landowners would purchase a portion of

this water to irrigate crops and their pleasure gardens. While poetry,

music, and conversation with friends and family all took place in garden

settings, they also provided a protected environment in which to grow

fruit and nut trees, vegetables, and flowers such as roses, iris, and

lilies. Most of the trees and plants in the Wagner carpet are rendered

in a botanically imprecise way, yet the profusion of foliage and

blossoms reinforces the impression of a delightful, perfumed bower.

Upper half of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

For an enclosed space, such as an actual Persian garden would have

been, the assortment of fierce and peaceable animals involves very

little violence. Only the lions attacking goats (to the right and left

in the upper end of the carpet, above) hint that danger could possibly

lurk here. Otherwise, even the cheetahs near the horizontal central

watercourse appear to want to play with the goats before them. Ducks fly

through the trees and swim in the channels, while peacocks stroll

beneath the trees. Fish of several types navigate the watercourses,

while rabbits, foxes, and wolves gambol through the foliage. Imagine

sitting on such a carpet inside a building in winter or in a grand tent

in the desert. The delightful, animated scene might just transport one

away from either excessive cold or heat. Add to that any one of a myriad

of Persian verses that liken a beauty (male or female) to a cypress

tree, or a wine cup to a rose, and one can understand how such a carpet

conjures up the romantic frame of mind of much of Persian poetry.

Unlike the more stylized garden carpets of the eighteenth century, the specificity of animal species and some trees and plants in this carpet may imply symbolic meanings that are more particular than simply that of paradise. For example, the poet Hafiz (1315–1390) refers to a love object (the cypress) and the tears of the lover (the canal):

Unlike the more stylized garden carpets of the eighteenth century, the specificity of animal species and some trees and plants in this carpet may imply symbolic meanings that are more particular than simply that of paradise. For example, the poet Hafiz (1315–1390) refers to a love object (the cypress) and the tears of the lover (the canal):

The phantom of the stature of his cypress stands constantly in my eye,

Because the place of the cypress is at the bank of the canal.[1]

While such verses refer to a lover and her or his beloved, they also

reflect the mystical love of the divine. Likewise, Jalal al-Din Rumi

(1207–1273) uses the rose as a metaphor for Divine beauty:Because the place of the cypress is at the bank of the canal.[1]

Every rose that spreads fragrance in the outward world—

That rose speaks of the mystery of the Whole.[2]

That rose speaks of the mystery of the Whole.[2]

Go to Met Website

Go to Met Website

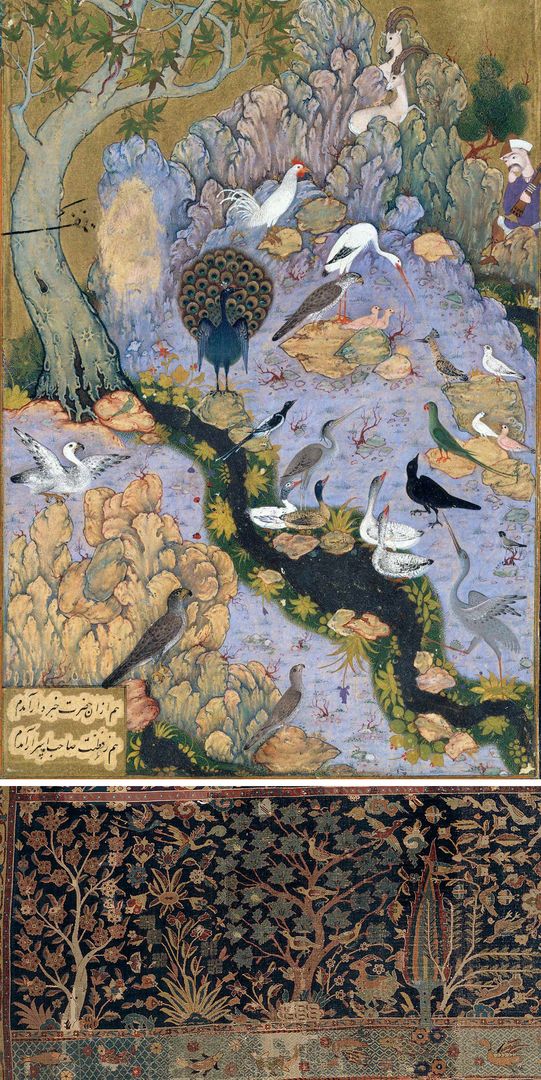

Top: Habiballah of Sava, "The Concourse of the Birds," folio 11r from a Mantiq al-Tair (Language

of the Birds) manuscript of Farid al-Din 'Attar, ca. 1600. Iran,

Isfahan. Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, painting: 10

x 4 1/2 in. (25.4 x 11.4 cm); page: 13 x 8 1/4 in. (33 x 20.8 cm). The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.11).

Bottom: Detail of the "Wagner" Garden Carpet

Animal symbolism may also have played a role in the Wagner carpet.

Birds are often characterized as being able to speak and are celebrated

in the poem Mantiq al-Tair (The Language of the Birds) by Farid

al-Din 'Attar (1145–1221), in which the hoopoe seeks to rally

twenty-nine other birds to set out in search of the mythical Simurgh,

a phoenix-like bird who lives at the end of the world. Although the

hoopoe is absent from the carpet, the birds depicted may include the

nightingale, a perennial favorite in Persian poetry, best known for its

attraction to the rose and its call when separated from its beloved

flower. Peacocks, which abound in the carpet, represent beauty as an

attribute of both the beloved and the springtime garden. Gray doves, on

the other hand, are partnered with the cypress, and their cooing, which

sounds like the word for "where" in Persian, represents the call for a

distant beloved.

Silk animal carpet (detail),

second half of 16th century. Iran, Kashan. Silk (warp, weft, and pile);

asymmetrically knotted pile, 94 7/8 x 70 1/8 in. (241 x 178 cm). The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913

(14.40.721)

Unlike the birds, the imagery of the four-footed animals in the

carpet may have a closer connection to the existing pictorial vocabulary

of animal combats in sixteenth-century carpets, and to the motifs of

animals in natural settings found in textiles of the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, than to poetry. Carpets featuring animal combats

were produced in a variety of techniques in the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries in Iran (above), and by the eighteenth century

poets were referring to the "lion in the carpet," confirming the

perennial place of the king of beasts in some classes of Persian rugs.

Although, when it was first made, the Wagner carpet most likely would have been larger and had different borders than it has now, the impression of glorious nature within a garden is no less powerful in its present dimensions (209 x 170 in.). Its flora and fauna coexist happily, calling to mind the court of the first Iranian king in the national epic, the Shahnama, in which all animals and man lived together in harmony. The abundance of blossoms evokes scented zephyrs and romantic verses, the perfect setting for springtime, captured in a walled garden for eternity.

Although, when it was first made, the Wagner carpet most likely would have been larger and had different borders than it has now, the impression of glorious nature within a garden is no less powerful in its present dimensions (209 x 170 in.). Its flora and fauna coexist happily, calling to mind the court of the first Iranian king in the national epic, the Shahnama, in which all animals and man lived together in harmony. The abundance of blossoms evokes scented zephyrs and romantic verses, the perfect setting for springtime, captured in a walled garden for eternity.

Notes

[1] Annemarie Schimmel, A Two-Colored Brocade (Chapel Hill, 1992), 164.[2] Schimmel, Brocade, 175.

Eternal Springtime: A Persian Garden Carpet from the Burrell Collection

On view from July 10 through October 7, 2018, in Gallery 462

Department:

Islamic Art

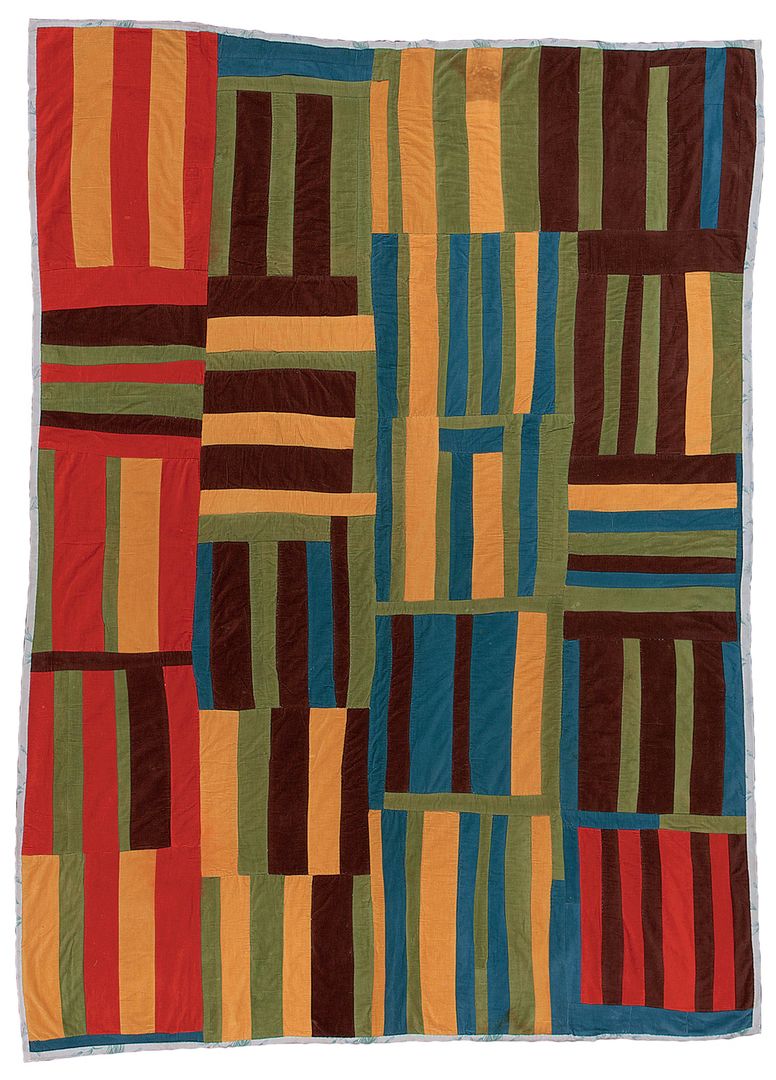

Gee's Bend quilts

I had the good fortune to see this show both at the Corcoran, with my good friend, Pam, and her friend, Lisa, both of whom make art, and who pointed out the brilliance of the color choices by these untutored women, & at Boston's MFA. (Can't believe it was that long ago.) Good to see the quilts have been memorialized in a book and paired herrewith 20th century art, something I think the MFA did a bit of.

Amish quilts, like the one on the left, were similarly compared to abstract painting, even though the makers had little exposure to these trends in contemporary art. Gee's Bend artists adapted traditional quilting patterns but improvised with the patterns and used materials that were readily available to them, like recycled denim work clothes. Left: Amish maker. Quilt, Split Bars pattern, ca. 1930. Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Wool and cotton, 87 x 77 in. (221 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jan P. Adelson and Joyce B. Cowin Gifts, 2004 (2004.26). Right: Annie Mae Young (American, 1928–2012). Strip Medallion quilt, 1976. Top: cotton and cotton-polyester blend; back: cotton-polyester blend; binding: self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 104 1/2 x 77 in. (265.4 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.57)

Just as the other artists in the show are working into today, the

quilters are still creating as well, though they may be second or third

generation. The most recent quilt we have in the collection is from the

2000s. Eighty-four-year-old quilter Lucy Mingo came to the opening of

the exhibition and said she still quilts with her friends four days a

week! It's very much a living tradition.

Rachel High: At the end of the essay, you discuss the difference between art and craft. What do both words mean to you? Are they mutually exclusive?

Amelia Peck: As a textile curator who has spent a lot of time studying and exhibiting women's work, I came to the conclusion in my essay that there is no difference, in my mind, between art and craft. Of course, there is textile art, which contemporary artists are making today with the intention that the finished product will hang in a museum, but throughout history, women were making very fine textiles that were intended to highlight their artistic talents, even if they weren't shown outside the home.

The women of Gee's Bend describe creating the quilts as a process of finding combinations of colors and patterns that pleased their eyes. My conclusion is that these quilts are art because the women of Gee's Bend had an intentional vision: they were composing artworks by putting pieces of various fabrics together, no differently than the other artists in the show would compose a painting or an assemblage.

Art on Its Own Terms: Author Amelia Peck on Gee's Bend Quilts in My Soul Has Grown Deep

July 16, 2018

Rachel High, Publishing and Marketing Assistant, Editorial Department

Rachel High, Publishing and Marketing Assistant, Editorial Department

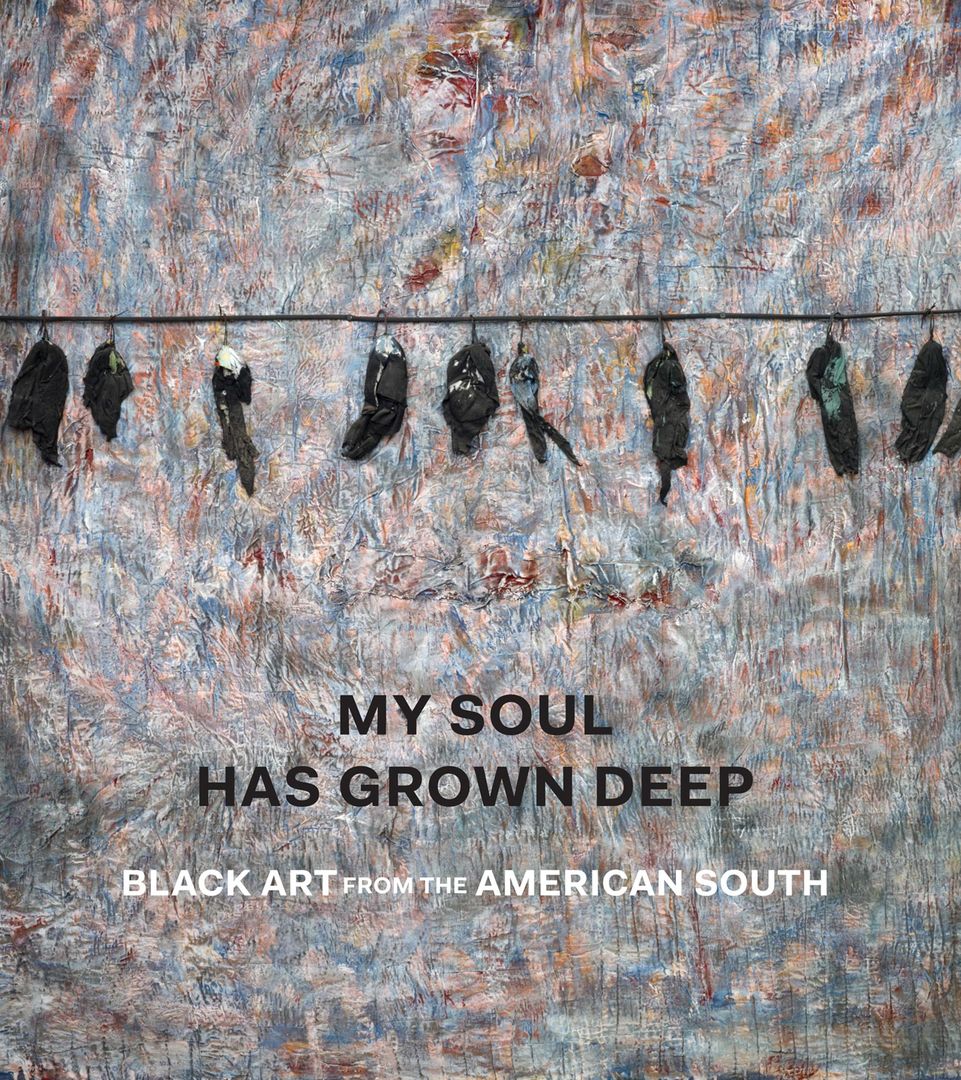

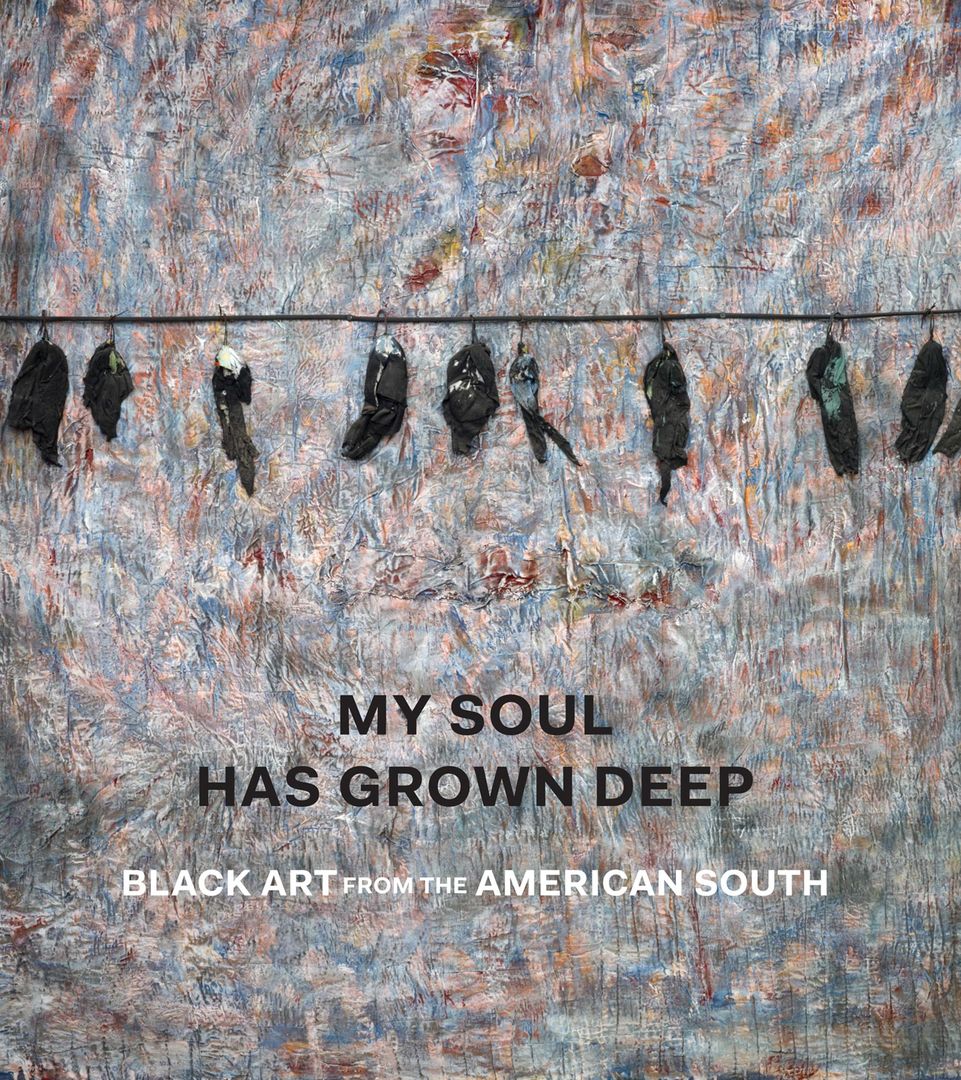

My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South,

by Cheryl Finley, Randall R. Griffey, Amelia Peck, and Darryl Pinckney,

featuring 112 full-color illustrations, is available at The Met Store and MetPublications. Cover: Thornton Dial (American, 1928–2016). The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly

(detail), 2007. Quilt, wire, fabric, and enamel on canvas on wood, 72 x

72 in. (182.9 x 182.9 cm). Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the

William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.5). © Thornton Dial

Recently published by The Met, My Soul Has Grown Deep: Black Art from the American South accompanies the exhibition History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation,

on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 23. The show and the

catalogue consider the art-historical significance of contemporary black

artists working in the southeastern United States, particularly those

working around greater Birmingham, Alabama.

The paintings, drawings, mixed-media compositions, sculptures, and textiles included in the book range from the profound assemblages of Thornton Dial to the renowned quilts produced in Gee's Bend, Alabama. In a departure from earlier scholarship, this remarkable study considers these works on their own merits, while also telling the compelling stories of artists who overcame enormous obstacles to create distinctive and culturally resonant works of art.

In a recent review of the catalogue, the Wall Street Journal praised Amelia Peck's essay on the Gee's Bend quilters, "Quilt/Art: Deconstructing the Gee's Bend Quilt Phenomenon," in which she questions some of the commonly held assumptions about these works of art. I had the opportunity to speak with Amelia about her essay, American traditions of quilting, and the slippery distinction between art and craft.

The paintings, drawings, mixed-media compositions, sculptures, and textiles included in the book range from the profound assemblages of Thornton Dial to the renowned quilts produced in Gee's Bend, Alabama. In a departure from earlier scholarship, this remarkable study considers these works on their own merits, while also telling the compelling stories of artists who overcame enormous obstacles to create distinctive and culturally resonant works of art.

In a recent review of the catalogue, the Wall Street Journal praised Amelia Peck's essay on the Gee's Bend quilters, "Quilt/Art: Deconstructing the Gee's Bend Quilt Phenomenon," in which she questions some of the commonly held assumptions about these works of art. I had the opportunity to speak with Amelia about her essay, American traditions of quilting, and the slippery distinction between art and craft.

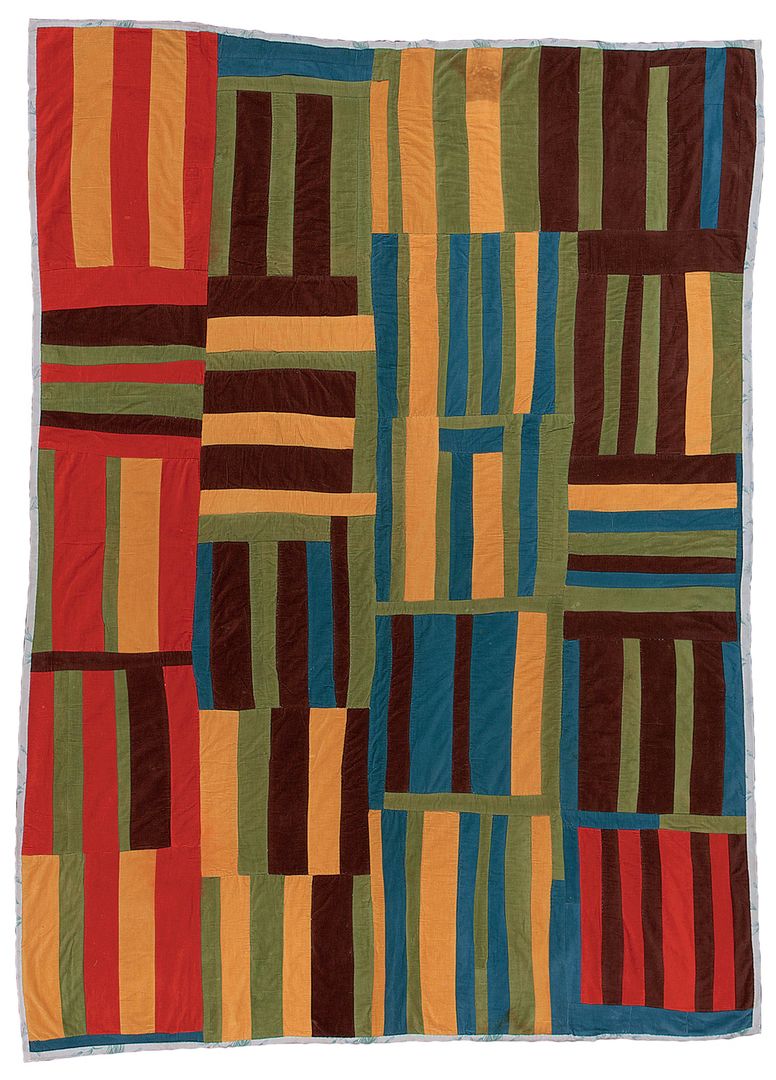

Barnett Newman's Concord and Loretta Pettway's Lazy Gal Bars quilt may share visual similarities, but they come from entirely different traditions. Left: Barnett Newman (American, 1905–1970). Concord,

1949. Oil and masking tape on canvas, 89 3/4 x 53 5/8 in. (228 x 136.2

cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund,

1968 (68.178). © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right:

Loretta Pettway, (American, born 1942). Lazy Gal Bars quilt,

ca. 1965. Top: cotton and cotton-polyester blend; back: polyester;

binding: self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 80 1/2 x 68

1/2 in. (204.5 x 174 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift

of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection,

2014 (2014.548.50)

Rachel High: The quilts featured in My Soul Has Grown Deep

first spent time on beds in Gee's Bend before The Met hung them on the

walls of its galleries. Women working outside of traditional art-world

paradigms created these compelling textiles. Both of these facts

traditionally precluded the quilts from being considered as works of

art. In asserting the value of the margin, it is often tempting to

compare it to the center—even if that is actually a superficial

comparison. Previous scholars have compared the Gee's Bend quilts to

abstract paintings. In your essay, you reject this interpretation. Why?

Amelia Peck: To say that they look like abstract paintings is an easy, though superficial, way to understand Gee's Bend quilts. The women making these quilts never saw the abstract paintings that their work supposedly references.

There's a marketplace component to this view; this comparison was an attempt to raise their value—I'm not talking simply about monetary value, but rather the validity of these quilts as works of art. Earlier generations couldn't see them as anything other than domestic. "Women" and "domestic" are uncomfortable categories for most classically trained art critics; a useful object made by women for the home that also happened to be beautiful was not considered art.

For a long time, critics compared graphic quilts to abstract art painted by men as an easy way to make sense of them and to make them into something more valuable than just a bed covering—more of a "real" work of art.

Amelia Peck: To say that they look like abstract paintings is an easy, though superficial, way to understand Gee's Bend quilts. The women making these quilts never saw the abstract paintings that their work supposedly references.

There's a marketplace component to this view; this comparison was an attempt to raise their value—I'm not talking simply about monetary value, but rather the validity of these quilts as works of art. Earlier generations couldn't see them as anything other than domestic. "Women" and "domestic" are uncomfortable categories for most classically trained art critics; a useful object made by women for the home that also happened to be beautiful was not considered art.

For a long time, critics compared graphic quilts to abstract art painted by men as an easy way to make sense of them and to make them into something more valuable than just a bed covering—more of a "real" work of art.

Amish quilts, like the one on the left, were similarly compared to abstract painting, even though the makers had little exposure to these trends in contemporary art. Gee's Bend artists adapted traditional quilting patterns but improvised with the patterns and used materials that were readily available to them, like recycled denim work clothes. Left: Amish maker. Quilt, Split Bars pattern, ca. 1930. Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Wool and cotton, 87 x 77 in. (221 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jan P. Adelson and Joyce B. Cowin Gifts, 2004 (2004.26). Right: Annie Mae Young (American, 1928–2012). Strip Medallion quilt, 1976. Top: cotton and cotton-polyester blend; back: cotton-polyester blend; binding: self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 104 1/2 x 77 in. (265.4 x 195.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.57)

Rachel High: Your essay made me realize how

innovative the Gee's Bend quilters are in adapting traditional quilting

patterns. You wrote that the Gee's Bend quilts in The Met collection

reference and blend five traditional patterns, and that "by breaking and

blending patterns, the designs are filled with action and vibrancy."

What is it about the Gee's Bend environment that made their innovations

possible?

Amelia Peck: I think it was a combination of things. These patterns were passed down through generations of Gee's Bend women. Patterns that were typical across the country in the mid-to-late nineteenth century were still being made by Gee's Bend quilters much later, into the twentieth century. That said, these traditional patterns were made less and less traditional over the years by the visual sensibility of the original quilters, who then taught their children and their grandchildren. They put their own particular spin on things. For example, the Gee's Bend quilters often used different materials than those used in more traditional quilts, and they mostly depended upon reused fabrics.

The myth of patchwork quilts has always been that all patchwork quilts are made from leftover scraps collected by women. That is not necessarily the case—in fact, it is usually not the case. In many nineteenth-century quilts, much, if not all, of the fabric was brand new. In the case of the Gee's Bend quilters, however, they really were cutting up old clothes and other readily available fabric, which they didn't have to buy new, to create their quilts. For the corduroy quilts, they used scraps left over from a large commission making cushion covers for Sears, Roebuck and Company in the 1970s. The Freedom Quilting Bee, a collective to which many of the Gee's Bend quilters belonged, organized that work.

Amelia Peck: I think it was a combination of things. These patterns were passed down through generations of Gee's Bend women. Patterns that were typical across the country in the mid-to-late nineteenth century were still being made by Gee's Bend quilters much later, into the twentieth century. That said, these traditional patterns were made less and less traditional over the years by the visual sensibility of the original quilters, who then taught their children and their grandchildren. They put their own particular spin on things. For example, the Gee's Bend quilters often used different materials than those used in more traditional quilts, and they mostly depended upon reused fabrics.

The myth of patchwork quilts has always been that all patchwork quilts are made from leftover scraps collected by women. That is not necessarily the case—in fact, it is usually not the case. In many nineteenth-century quilts, much, if not all, of the fabric was brand new. In the case of the Gee's Bend quilters, however, they really were cutting up old clothes and other readily available fabric, which they didn't have to buy new, to create their quilts. For the corduroy quilts, they used scraps left over from a large commission making cushion covers for Sears, Roebuck and Company in the 1970s. The Freedom Quilting Bee, a collective to which many of the Gee's Bend quilters belonged, organized that work.

Scraps

of corduroy left over from the Sears, Roebuck and Company commission

organized by Freedom Quilting Bee make up this quilt. Willie "Ma Willie"

Abrams (American, 1897–1987). Roman Stripes quilt,

ca. 1975. Top: cotton; back: cotton-polyester blend; binding:

self-bound, back turned over front and stitched, 93 1/4 x 70 in. (236.9 x

177.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls

Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett. 2014 (2014.548.38)

There was also an element of necessity in the quilters' innovations. I

read about and talked to some of the women from the Gee's Bend area

when researching for the catalogue; I don't want to generalize too much,

but a lot of the women had very large families and lived in houses

where they really needed to make these quilts to keep their families

warm. The Gee's Bend quilters weren't going to spend a year piecing

together lots of tiny bits of fabric to make an absolutely perfect,

predefined pattern. Instead, they worked pretty quickly and used larger

pieces of fabric if available. They improvised with what they had and

created patterns that were very decorative and attractive but were not

the laborious and overly intricate patterns created in wealthier

communities, where women had more leisure time.

Rachel High: Unlike the objects in the rest of the book by the artists of the Birmingham-Bessemer group, which mostly date from the last fifty years, the Gee's Bend quilts go as far back as the 1930s. How are the quilts in dialogue with the more recent works featured in the publication?

Amelia Peck: Until we started installing the show, I didn't realize how many of Thornton Dial's works incorporated textiles. The work by Dial on the cover of the book, The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly, is actually painted on a quilt. Ronald Lockett's great aunt Sarah Dial Lockett was a famed quilter. The quilts were very much a part of the local art world in the area of Alabama where most of these artists lived. Even though the Gee's Bend quilts have been shown separately from these paintings and sculptures in the past, the male and female artists knew each other's work.

Rachel High: Unlike the objects in the rest of the book by the artists of the Birmingham-Bessemer group, which mostly date from the last fifty years, the Gee's Bend quilts go as far back as the 1930s. How are the quilts in dialogue with the more recent works featured in the publication?

Amelia Peck: Until we started installing the show, I didn't realize how many of Thornton Dial's works incorporated textiles. The work by Dial on the cover of the book, The End of November: The Birds That Didn't Learn How to Fly, is actually painted on a quilt. Ronald Lockett's great aunt Sarah Dial Lockett was a famed quilter. The quilts were very much a part of the local art world in the area of Alabama where most of these artists lived. Even though the Gee's Bend quilts have been shown separately from these paintings and sculptures in the past, the male and female artists knew each other's work.

The

quilters and the other artists in the catalogue worked in the same area

and shared ideas. Many of the male artists also used textiles in their

work or were influenced by the aesthetics of quilts. The catalogue's

cover features a painting by Thornton Dial that uses a quilt as its

base. Ronald Lockett's great aunt was a well-known quilter, and his work

shows similar interest in found materials and in the composition of the patterns of local quilts. Left: Ronald Lockett (American, 1965–1998). The Enemy Amongst Us,

1995. Commercial paint, pine needles, metal, and nails on plywood, 50 x

53 x 3 in. (127 x 134.6 x 7.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett

Collection, 2014 (2014.548.10)

Rachel High: At the end of the essay, you discuss the difference between art and craft. What do both words mean to you? Are they mutually exclusive?

Amelia Peck: As a textile curator who has spent a lot of time studying and exhibiting women's work, I came to the conclusion in my essay that there is no difference, in my mind, between art and craft. Of course, there is textile art, which contemporary artists are making today with the intention that the finished product will hang in a museum, but throughout history, women were making very fine textiles that were intended to highlight their artistic talents, even if they weren't shown outside the home.

The women of Gee's Bend describe creating the quilts as a process of finding combinations of colors and patterns that pleased their eyes. My conclusion is that these quilts are art because the women of Gee's Bend had an intentional vision: they were composing artworks by putting pieces of various fabrics together, no differently than the other artists in the show would compose a painting or an assemblage.

Sunday, August 12, 2018

Spiritual comfort

If you have need of some spiritual comfort, give a listen to this week's episode of episode of Kristin Tppett's interview with the late Joe Carter. His singing of the spirituals they talk about is second to none : https://onbeing.org/programs/joe-carter-the-spirituals-aug2018/ Mr. Carter died in 2006. Unfortunately I couldn't find an obit.

Here's the transcript:

Krista Tippett, host: This hour, an exuberant experience of conversation and singing the spirituals. There are nearly 5,000 spirituals in existence. Their organizing concept is not the melody of Europe, but the rhythm of Africa. They were composed by slaves, bards whose names we will never know, and yet gave rise to gospel, jazz, blues and hip-hop. Joe Carter lived and breathed the universal appeal and the hidden stories, meanings, and hope in what were originally called “sorrow songs.”

Joe Carter: What we're talking about is human suffering, and how do we survive when the worst happens? What are the mechanisms? I can sing "Motherless Child" in Siberia; they know what it means. They've been through hell. I can go to Scotland and Ireland and Wales and sing these. They understand the sentiment. The songs have become symbolic, I think, of that universal quest for freedom, that yearning for freedom, and that part of us that says, "I will not be defeated."

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

This was one of our first weekly shows and it’s still one of our most beloved. Joe Carter remained relatively unknown through his death in June, 2006. But he performed for more than 25 years in opera and musical theater and he portrayed Paul Robeson in a one-man musical. I spoke with him in a music recording studio in 2003, with his pianist Tom West nearby for whenever Joe might feel called to burst into song.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me what you think of when I ask the question about how this music played a role in your earliest religious life, and what songs, or what song, comes into your mind first and why.

Mr. Carter: It takes me back to my childhood in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and my church, which was Union Baptist Church, the main black church in Cambridge at the time. We didn’t have spirituals in the church, and we didn’t have African-American gospel music. It was a period of time when there were a lot of African Americans who were saying, we’re not connecting to our history. We want to show everyone that we can be integrated. So we were singing European anthems, so I never heard it in my church except when there was a baptism. And when the preacher would go into the baptismal pool and he’d come out, he’d immediately begin to sing [singing] “Everybody sing amen, amen, hallelujah, amen, amen, amen.” There was no pipe organ, no piano, he was just singing a cappella and the church would begin to rock. And as a child I remember — wow, what is that? There’s something special about that song, about that music — and I was always excited when I got a chance to hear it, but I didn’t get to hear it very often in my church.

Another time I heard it was on recordings. We had an old scratchy — I think it was a 78 recording, and it was a choir called the Wings Over Jordan Choir, and they were an African-American radio choir in the early days. And it was something we didn’t hear very often. They were spirituals.

Whenever we played this record it was almost a total hush in the room, in the family, because it was the story of Mary McLeod Bethune, who was a relative of ours, and it tells the story of how this little girl was the first one born free in her family, how she wanted to learn to read and write, and in the background you’d hear the Wings Over Jordan Choir singing spirituals.

[music: “I Will Trust In The Lord” performed by the Wings Over Jordan Choir]

And somehow it was during those experiences I realized there was something very special about this music that was different than jazz, blues, and rock and roll that we played on the record player, or even some of the gospel songs. This was something that was even more powerful. And I think I had developed a real desire to learn about it.

Ms. Tippett: So tell me what years are we talking about — when were you born, when were you growing up?

Mr. Carter: I was born in 1949. So I was a child of the ’50s and the ’60s. And then the civil rights movement came along, and everyone was singing spirituals. And in Cambridge we had all the folk singers. And when I was 15 years old I got into a folk singing duo with my best friend at the time, with David Levithan who’s Jewish, and David told me, "Joe, your people have wonderful music." And this was the first time I'd ever heard someone say that. So he wanted to come to my church to hear the music. So he came to Union Baptist Church on a Sunday morning and heard Bach. He said, "Joe, that ain't it." [laughs]

And so I began to search for places that I could share this music with David and hear it myself. So we would go into the ghetto in Boston and we’d go around little store-front churches and we’d go, “This is it! This is it! You hear the tambourines beating and the people? Oh, yeah.” [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Oh gosh, there’s so much I want to pursue here. First of all, it’s very intriguing to me that you started on that journey with a Jewish friend because I think so many of the stories that the spirituals captured came from the Hebrew Bible, the story of the exodus.

Mr. Carter: Absolutely, that's true. We had a folk-singing duo, David and I, called the Dithy Ramble Duo. And we sang “This Train Don’t Carry No Gamblers” and those songs that were popular in the ’60s. And that was kind of a beginning.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me what your family’s connection was with the world in which the spirituals were created, which was the world of black slavery.

Mr. Carter: I think it’s only as an adult I really began to understand that because my parents were very careful not to talk about their pains and the things that the ancestors went through because they didn’t want us to grow up with, so-called, a chip on our shoulders. They want us to be free and to realize that prejudice was an evil thing and we must not let it be found in us. But later I realized my grandparents were born right after slavery. So all of my great-grandparents were born slaves, my grandparents grew up on the plantation, my parents as children were on the plantation as share croppers and moved to the North mainly to flee the persecution of racism and brought us to a place that was an international community. And every once and a while I would hear my mother or my father singing a little song very quietly, they wouldn’t sing openly — or my grandparents. And I'd say, “What’s that song?” “Oh nothing, nothing, nothing.”

Ms. Tippett: Do you think that these were songs that they really carried around inside them. They weren’t consciously humming them.

Mr. Carter: Yeah they did. I think they heard them from their parents and their grandparents and they were just songs that they sang for comfort.

Ms. Tippett: So I think — and it was only as I prepared to speak with you — that we celebrate this music now, right? American culture as a whole celebrates this music. We don’t think very hard or very often about where they came from and how that is speaking to us also through this music. And it was also — this question that James Weldon Johnson raises in the book that you gave me from 1925, the book of spirituals, about who wrote this music — that there must have been bards, that there were great artists at work. Is there folklore around that that came down to you through your family? Is there a memory of that? What do you think, or what have you learned?

Mr. Carter: Well, I discovered a few things as a teenager. I met a woman by the name of Jessie Anthony who was — I think she was over 80 when I met her. And somehow, she was coming to our church. And we young people would go to her house to collect her, to bring her to church and so on. Well, here was an African-American woman whose parents were slaves in Virginia. And she sang the spirituals. And she'd heard me sing in church, so she just sort of took me under her wing. And she was going to teach me these songs. And she had a suitcase full of stories that she'd collected over the years of the spirituals. And she would tell me, she'd say, “Child, when they sang this song, this is what they were talking about, you know? A lot of people don't know this.” And she had stories for every song.

Ms. Tippett: OK, tell me a story.

Mr. Carter: One of the stories I seem to remember that she told, it was about — Emancipation Day had come. There was a group of former slaves, now, on an island off the coast of South Carolina. My parents were from South Carolina, all my family. And they were waiting for the emissary of the government to arrive in his little boat to tell them that they had received the deeds to their land, because the government had promised them not only freedom, but 40 acres and a mule. This was going to be a great, wonderful day.

And the former slaves had gathered together on the island waiting with bated breath. And finally, they saw the boat of the officer approaching. And they could tell, even from the distance, that his face was not happy and his countenance was somewhat sad. And they said there was a groan that just came from the crowd. And one of the older women from the crowd just stood up and began to make up a song on the spot. Do you want me to show you what that song is?

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, I do.

Mr. Carter: I’ll go to the piano. She sang,

[singing] Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows but Jesus

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory, hallelujah

And then she spoke, looking to the people around her, she said,

Sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down

Oh, yes, Lord

Sometimes I’m almost level to the ground

Oh, yes, Lord

Oh, nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows but Jesus

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory, hallelujah

Ms. Tippett: And sorrow songs, is that what the spirituals were called routinely?

Mr. Carter: Yeah, that's what I'm told.

Ms. Tippett: And it does connote — it connotes what's in the music, but it connotes something different from the title "spiritual."

Mr. Carter: Mm-hmm. Because they were the expression of the great pain and the sorrow. But at the same time, they were always looking upward. They were always reaching. There was always some level of hope, as opposed to the concept of the blues. The blues was just singing about your troubles, and there was no hope. But there's always the glory hallelujah someplace saying, "Oh, and on that glory hallelujah, then we fly." So in the midst of the night, we can fly away to freedom while we're singing these songs. And this is another.

[singing] I am a poor pilgrim of sorrow

Down in this wide world alone

No hope have I for tomorrow

I've started to make heaven my home.

Sometimes I'm tossed and driven, Lord

Sometimes I don't know where to roam

I've heard of a city called heaven

I've started to make heaven my home

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today experiencing the hidden stories, meanings, and hope of the spiritual. This is one of our earliest and most beloved shows, with the late, singular musician and humanitarian, Joe Carter.

Ms. Tippett: It seems to be grounded in the experience of sorrow, but making a connection with that, between that and the larger human spirit, and the larger experience of God, which is not just about the sorrow.

Mr. Carter: Yeah. I think that the sorrow became the entrance, the open door, into a whole new world of experience. The slaves could not experience the normal world. They couldn't go out and go shopping. They couldn't buy a house. They couldn't do all the things that the normal white person did. They were slaves, you know? They were whipped, and they had chains. And they found a secret door to take them into that world where the tears are wiped away.

Ms. Tippett: But the tears are cried first, aren't they?

Mr. Carter: Yeah.

Ms. Tippett: You talked about the secret power of these songs. And I think so much of what we're learning now in our advanced day is how important it is to embrace suffering in life in order to move forward.

Mr. Carter: Yeah.

Ms. Tippett: And maybe they did not have a choice.

Mr. Carter: No, they didn't.

Ms. Tippett: But it's almost like there's healing in that moment, even though it doesn't take the pain away.

Mr. Carter: And that's one reason, I think, that African-American religion and culture has become so powerful in the world. One of the things that I think about when I think about this body of music. I realize that it was the foundation for most other American music. And this music has changed the face of music in the 20th century. And the story behind the creation of the spirituals, it's a miraculous story. Normally, when you hear the story of African-American music in a documentary or something, you go back to Ella Fitzgerald or Louis Armstrong. And I say, “well, that's great. But if you really want to know the story behind the story, find out who Louis' grandmother was and what she was singing. What were the songs he learned when he was a baby? And what were the messages of those songs?”

And the thing that we find is that in the midst of all of the most horrible pain, some of these powerful individuals lived transcendent, shining lives. They were able to rise up above. They were able to be loving and forgiving in the midst of it all.

Mammy was taking care of master's baby. It was mammy, not master's wife, that was nursing that little baby. Mammy could have poisoned the child. She could have smothered the child. But she loved that child like it was her own child. Because there was something in her faith that said, "You're supposed to be loving. You're supposed to be kind. You're supposed to be forgiving. And there's no excuse if you are not." We have songs like — the interesting thing — you don't find mean-spirited sentiments in the spirituals. They're the most noble sentiments.

Now, you find a song like this: [singing] “It's me, it's me, it's me, oh, Lord, standing in the need of prayer…” Not my brother, not not my sister, not the preacher, not the deacon, not the doctor, not the lawyer, not the master? Wait a minute. These are people who were victims. They were in the midst of the most horrible situation, but they said, “I'm taking responsibility for who I am today, and it's me standing in the need of — I'm the one that has the proud heart today. Come and fix me.”

Ms. Tippett: And again, I mean this is not only sound theology and psychology, it's extremely mature spirituality, right?

Mr. Carter: Yeah.

Ms. Tippett: What was it that came together in the lives and the spiritual sensibility of those slaves that connected them so powerfully to — really those are the best attributes of Christianity that you're talking about. They're not often practiced.

James Weldon Johnson talked about this as the verging of the spirit of Christianity with the vestiges of African music or an African sensibility. Do you have any ideas about what made that such a special fusion?

Mr. Carter: Well, I've thought about it a lot, and one thing that occurs to me, if we go back to the cultures of the slaves that came from many different African nations and languages, one thing they had in common was they believed in a supreme deity. But they believed he was very busy and very, very holy, and in order to get to him, you had to go through the ancestors. It wasn't very dissimilar to the way Europeans felt with the saints, and so on. When slavery took place — and there was also this concept that you commune with deity with magic, shining songs. If your songs come forth with great fervor, you not only reach deity, but deity comes and possesses you, becomes part of you, and gives you the strength to do whatever you've got to do to win your battles, to harvest your crop.

And when people were taken suddenly as slaves, when they were literally kidnapped from their normal lives, whatever those lives were, they were taken away from the land of their ancestors. The spirit of the ancestors couldn't cross the water. And so, when they were taken on these boats away from their homes, they experienced the most deep desolation possible, because not only were they being removed from their friends and kindred, but they were being removed from their God. And they had no way to get to God, because the ancestors were way back in Africa on the land.

And I imagine when the slaves heard about this Jesus — now, the master's religion, first of all, you've got to realize this: They were not impressed by the master's Christianity, may I say.

Ms. Tippett: Well, right. This is why it's even surprising to me that they adopted Christianity.

Mr. Carter: Exactly, because they saw all of the brutality, they saw all the hypocrisy, and were the brunt of it. But they heard about this Jesus, this man of sorrow who suffered, and they identified. And then they were told that Jesus is the Son of the High God. “No. Wait, the Son of the High God? We can get to the High God through this guy? And his story sounds like our story? He's born in terrible circumstances, he's mistreated. He's finally abused and killed. My goodness. Maybe He will carry us to the High God.”

[music: “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” performed by Tom West]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more conversation and song with Joe Carter. Subscribe to On Being on Apple Podcasts to listen again any time and discover everything we create. Watch your feed in coming days. We’re going to be releasing the songs Joe was singing this hour for you to download. They were never made available as an album in his lifetime.

I'm Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, for the anniversary of Joe Carter’s death, we’re returning to my 2003 conversation with him — one of our very first shows and one of our most beloved. Joe embodied the beauty, sorrow, and hidden meanings within the spirituals, songs composed by nameless bards in slavery, and yet a tradition that gave us gospel, blues, jazz, and hip-hop.

Ms. Tippett: Were there songs reaching back to the ancestors? Do you think they felt that, also, that old belief that was planted in them of their songs reaching to God?

Mr. Carter: I think in the early days of slavery, yes. Because for a long time there were a lot of ancestors from Africa who were still there on the plantations. So they got that sense.

For example, with Mary McLeod Bethune — her grandmother came over from Africa with two sisters, and she remembered the songs and stories and sang those songs to the children. Now nobody in my family now remembers any of the songs, but we have the stories of her singing the songs to the children and so on. And it was through the songs that the faith was transmitted.

Ms. Tippett: Really, it’s taking the story whole and passing it on. It’s pretty good bible study.

Mr. Carter: And then the story of slavery.

Ms. Tippett: The exodus. Being captive in a foreign land.

Mr. Carter: Yes. The Jews in Egypt. “Go down, Moses, way down to Egypt land and tell old Pharaoh, ‘Let my people go!’” And sometimes I imagine how some of those songs were used and I imagine someone on the plantation, the master, who is always very happy when he hears the slaves singing because he knows where they are, he knows they’re not escaping, as long as he can hear them. An old master comes out one day. He says, “Hey, Joe. Big Joe. I don't hear nobody singing down there. You guys strike me up one of them good, old spiritual songs. You know how I like them. Give me one of them good, old songs.” And often when I go to the schoolchildren, I have them sing with me. I say, “OK. Now pretend you're going to be — you're all slaves, OK? And master wants us to sing a song, but we don't really want to sing for master, do we?” “No. No, we don't.” I say, “Well, I'll tell you something. Master loves our singing, but he doesn't listen to the words we say. He doesn't have a clue. So we can say anything we want. So, let's give the master a good old song.”

Ms. Tippett: What do you sing with the kids?

Mr. Carter: [singing] When Israel was in Egypt land,

Let my people go!

Oppressed so hard they could not stand,

Let my people go!

Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land

And tell old Pharaoh, Let my people go!

And after we go through the song, they go, “Hey, old master, how was that one?” [laughs]

One of the connections also that I learned about that period of time from my grandparents was, my grandfather was a storyteller. And he would regale the family, every time we were together, with slavery stories. That's what he always talked about. And there was a slave by the name of John who was the star of all of these stories. And you never knew whether the story was true or not, but it was always funny, and it got your attention, and Grandpa was a good storyteller. There was also always a moral at the end of the story.

But the one theme that went through all of these stories was that John had outsmarted the master. He was always ahead of the master.

So there was this concept — the master doesn't really understand us. We play a role for him and he sees us in a certain way, and we’ll play that role as much as we can so that we won't get whooped. So we’ve got to understand his thinking, but he can never understand our thinking. And so, the spirituals were — all of the spirituals, all of the songs were masks. As well as these transcendent, wonderful moments. They were also signals for escape.

For example, we’re gonna do another song now, which goes right along with what I was just… This was one of my grandmother's favorite songs.

[singing] Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus

I've got to steal away, steal away home

I ain't got long to stay here

My Lord He calls me, He calls me by the thunder

The trumpet sounds within my soul

And I ain't got long to stay here

Green trees are bending, poor sinner stands a tremblin’

The trumpet sounds within my soul

And I ain't, I ain't got long to stay, to stay here

It's like you get into the stream of that living water. And there's no past, present, and future. It's just right now, and right now everything is all right.

You know, there's a story about Elijah and a woman whose son died. She had received this son as a miracle, actually. And the prophet told her that she was going to have this son at a certain time and she did, and the son dies. And she says, “Send for the man of God. Send for that prophet.” And Elijah sends a servant. She says, “No, no, no. I want to see the man. Now, you gave me the promise, I have a child, and my child has died. I'm having a tragedy right now.” And when Elijah rode, coming close to her, he said, “Woman, how is it with thee?” She said, “It is well with my soul.”

And there was something that you can find even today in those, especially the older people who really have faith, you say, “How are you doing?” And you just see that smile. And it doesn't say that I'm doing OK. It doesn't say that everything's OK in my life. Sometimes they'll say, “I'm blessed.” Sometimes they'll say, “It is well.”

So the sense of well-being does not depend on whether things are good or bad or up or down because, if we had to live that way as slaves, we would constantly be buried underneath the ground, because the circumstances were so horrible and so bad we had to find, as I say, that secret door.

Ms. Tippett: We talked about how there was this subversive power of the words of the spirituals, saying things which really contradicted the interests of the masters, for example. But also there were more overt codes and real practical references in some of the spirituals. And give me an example of that, where there was almost a secret language.

Mr. Carter: “Steal Away To Jesus.” And when someone said, [singing] “I ain't got long to stay,” everybody knew, hey, I'm going to be escaping tonight, and I want you to be supporting me.

Someone is going to meet us on the other side of the river. “Green trees are bending, poor sinner stands a-tremblin’.” And maybe they had a signal where someone would shake a leaf in a branch of a tree across the river and you'd go on to safety to the Underground Railroad, hopefully.

“Swing low, sweet chariot, coming for to carry me home. I looked over Jordan, what did I see?”

Ms. Tippett: Wait, wait wait. “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” — what's going on there that's not overt?

Mr. Carter: Well, first, "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" was a death song, as most of them were in some way. And it was often sung when a child died. It was a way to evoke one's dignity, to say, even though I'm a slave, God has to send a golden chariot down from the sky. I'm going to have dignity. My child's going to have dignity. “I looked over Jordan and what did I see? A band of angels coming after me, coming for to carry me home.”

But then later you get, “If you get there before I do, tell all my friends I'm coming up there too.” So the master never knew what they were singing about. You see?

Ms. Tippett: I did not know that.

Mr. Carter: So I think at some point someone realized, "Maybe I don't have to die in order to have a little heaven." Freedom. And, of course, they thought that if they got to the Mason-Dixon line and crossed, they would have true freedom. And then, unfortunately, they got across the Mason-Dixon line and still found there was oppression, and found that somehow they had to revert back to the original spiritual meanings of the songs because the political meanings never delivered them.

[singing] Swing low, sweet chariot, comin' for to carry me home.

Swing low, sweet chariot, I said it's comin' for to carry me home.

Well, I looked over Jordan and what did I see comin' for to carry me home.

Well it was a band of angels comin' after me, comin' for to carry me home.

If you get there before I do, comin' for to carry me home.

Tell all my friends I'm comin' up there too, comin' for to carry me home.

Why don't you swing low, sweet chariot, comin' for to carry me home.

Oh, swing low, sweet chariot, oh, it's comin' for to carry me home.

It's comin' for to carry me home.

Oh, it’s comin’ for to carry me home.

Ms. Tippett: I can do a much more whimsical listen knowing what you just told me about some of the practicalities and codes behind that.

Mr. Carter: And I think there were so many of the songs, even “Wade in the Water”: “God's going to trouble the water,” another image of people going to the river to be baptized and also going to the river to escape to freedom. And the story was that a certain season, the angels would come and trouble the water, as they say, which, I don't know, they put their wings in or their toenails or whatever. But whatever happened, once they touched the waters, if you got in the water, and you were sick, you'd be healed.

So here's this guy, 38 years he's been going. And Jesus comes by and says, “What's your problem?” He says, “Can't you see? I'm a lame man. And every time the angels come to trouble the water, somebody gets in before me.” And Jesus said, “Do you want to be healed?” “Well, yes. Of course, I do.” “Then take up your bed and walk.” They loved this story, because this was about self-sufficiency. We are not victims. We're powerful individuals, and we are people of faith. And so they sang — let me just do a little bit of that song.

[singing] Wade in the water, wade in the water, children

Wade in the water, God's gonna trouble the water

Who's that yonder dressed in white, God's gonna trouble the water

Well, it must be the people called the Israelites, God's gonna trouble the water

Children, wade in the water, wade in the water, children

Wade in the water, God's gonna trouble the water.

Well who's that yonder dressed in red, God's gonna trouble the water

It must be the people that Moses led, God's gonna trouble the water

Children, wade in the water, wade in the water, children

Wade in the water, God's gonna trouble, gonna trouble the water

Ms. Tippett: What this makes me think of is how the politics of freedom can actually distract from this inner freedom and dignity, which the slaves possessed and which we find so expressed in this music even today.

Mr. Carter: And maybe in the same sense that sometimes religion can distract from spirituality. You get a structure, a form. You get a program, and somehow, after a while, the real thing is as elusive as the Holy Grail.

Ms. Tippett: Right. And you can lose this sense that these slaves who created this music obviously had that — at every moment, they were full of grace. All was well with their souls no matter what was going on around them, no matter what rights they had or what their legal status was.

Mr. Carter: No, it must be said that there were certainly slaves who were trying to escape, slaves who were willing to get involved in revolution and insurrection and so on. But I think the larger community had a spiritual identity that guided them.

Ms. Tippett: And we have to be so careful not to be glorifying slavery, right? So what are we talking about here? What are we getting at?

Mr. Carter: I think what we're talking about human suffering, and how do we survive when the worst happens? What are the mechanisms? And I think that African Americans have shown the world, and other peoples have done it, too. Other peoples are doing it all the time, and it's the same process. It doesn't matter who the people are. It doesn't matter whether the song is an actual song of notes and music or whether it's the spirit of a people expressed in some other way, but you'll find — for example, when I sing these songs, I can sing "Motherless Child" in Siberia; they know what it means. They've been through hell. I can go to Scotland and Ireland and Wales and sing these. They understand the sentiment.

As a matter of fact, you go to Wales right now, you'll find African-American spirituals in Welsh in the Welsh hymnbook, part of their worship. So the songs have become symbolic, I think, of that universal quest for freedom, that yearning for freedom and that part of us that says, "I will not be defeated."

Let me do a little bit of “Motherless Child.”

Ms. Tippett: That’s the one I was humming at my computer this morning as I was making notes for this. I’m not sure why. [laughs]

Mr. Carter: [singing] Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child

Oh, Lord, sometimes I feel like a motherless child

A long ways from home

A long ways from my home

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today, experiencing the hidden stories, meanings, and hope of the spiritual. This is one of our earliest and most beloved shows, with the late, singular musician and humanitarian Joe Carter.

[music: “Motherless Child” performed by Joe Carter]

Ms. Tippett: The paradox of the spirituals in their context of slavery was that they gave themselves over, in some sense to suffering and to the hardness of life and really to an essential powerlessness. This is where we are; this is where we live. But there was an "and." "And, I am beloved, I'm graced, I am blessed, I have dignity, I'm alive, and what I experience now is not all there is." There's a surrender and there's an incredible power at the same time in the spirituals, and when life is halfway better, maybe the surrender goes away and the power is diminished, too. Am I making any sense?

Mr. Carter: Yeah, that's one of the horrible problems that we have to deal with, with the whole issue of progress, you know? Because in the process, we may lose something. But you know something? Because I have been living with these songs, these songs have become the strength of my life. Because I realize even though I am not in slavery, as my grandparents or great-grandparents were, I deal with all of the difficulties of life that nobody escapes.

Ms. Tippett: No. And even somebody who's perfectly free and perfectly rich and perfectly powerful in the world's terms doesn't escape from suffering, right?

Mr. Carter: That's right. And the worst kind of bondage is that which takes place in the inside. When we look back to the slavery days, we were bound, but it was the master who was really the slave. And I think some of us understand that now. But I experience in my own life great strength from telling the stories and looking back, because I see what they went through, and I haven't experienced anything like what my ancestors did. And I complain about everything.

Ms. Tippett: I wonder if it is at all disturbing to you that this music with its sensibility has, is considered now to be a defining part of American culture as a whole? You could say maybe that it's been co-opted, embraced. Does that bother you? Because that necessarily takes it out of its context, doesn't it? I mean, is it OK for a white person to celebrate this as much as…

Mr. Carter: I think it's a good question. And my answer is this: When any music or art becomes this transcendent thing that helps people through, it then becomes a property of the universe. It becomes a property of the world. And to tell the story of the spiritual, it's not an African story. It is an African-American story. It's the blending of the two cultures.

And the fact that George Gershwin was influenced greatly by the spirituals, I think it's a wonderful thing that this man could reach out of his neighborhood, go down to South Carolina and listen to the elders sing and come back and say, "This is a treasure." And then translate that through his genius and give to the world as so many others have. There are many European composers like Dvořák who were influenced by this music. And today — it's true with any kind of art — there has to be the sensitivity of the person who is observing and participating. And some people don't get it no matter what you do. And there are other people, you don't have to say anything, and they get it from the get-go.

And one of the things I would say about the development of African-American music and culture — the powers that be found it much more attractive to promote the blues and to promote the image of the black man singing the blues with a bottle of wine in his back pocket singing about less-than-noble sentiments, while we had this whole treasure. And the Paul Robesons and the Marian Andersons and others who came and brought this music forth, they didn't make the big commercial successes. Well, Robeson, and Anderson did for a while, but they're among the few. In order to make a commercial success, you've got to sing soul, you've got to get away from anything that is spiritual and change the message.

Ms. Tippett: Soul as opposed to spiritual. That's interesting.

Mr. Carter: I just have a certain personal feeling about it because we still have a problem, because there are still people who don't want to tell the truth about who we are. And if the truth is really told, then you've got to go back and tell the story of the love and the forgiveness and the power of many of the ancestors. They weren't all loving and forgiving. Some of them were mean-spirited. Some of them did whatever they had to do, I'm sure. But as a national identity, this music became the embodiment of a spirit of goodwill, a spirit of forgiveness, a spirit of "I'm going to survive no matter what."

Ms. Tippett: Dignity. That's the word that keeps coming up.

Mr. Carter: And by the way, this woman that I told you about, Jessie Anthony, she was the most dignified soul I'd ever met. The last time I saw her, she was, I think, 88 years old. Her parents were born slaves. And she began to sing the spirituals. She sang at the Boston Public Library, she sang at Harvard, demonstrating the music. And she said, "Joe?" I said, "Yes, Ms. Anthony?" She said, "I want you to go into my bedroom and look under my bed and tell me what you see there." And so I went into her bedroom. I said, "You got a suitcase." She said, "Yes, I do, child." I said, "What's in the suitcase?" And she smiled. She beamed at me.

She said, "In that suitcase, I've got my going-home clothes. Ooh, I've got a beautiful dress in there. Jesus is coming for me any day, don't you know, child?" And she just started laughing. I'll never forget that image. Here was someone who'd gone through all of the changes in culture and society, and now was living in an elder apartment complex in Boston, all of her children in Washington, D.C., and everything. And she was still singing her songs. And she was holding her head up high every place she went. She was the kind of person who just commanded your respect. And when the young people — whenever we'd go to her house, she would tell us the stories of these songs and everything. And then, she would always end singing one little song. Give me a C, Tom.

And she'd sing, "Children, if you don't remember anything I've told you, if you don't remember any songs that I've sung for you, I want you to remember this one."

[singing] Be ready when he comes

Be ready when he comes

Be ready when he comes

Oh, Lord, he's coming again so soon

Now, Joe, you be ready. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Thank you so much, Joe Carter.

Mr. Carter: It is my pleasure to be here. Thank you.

[music: “Let The Work That I’ve Done Speak For Me” performed by Joe Carter]

Ms. Tippett: Joe Carter was a teacher, performer, and traveling humanitarian. He died at the age of 57 of leukemia on June 26th, 2006.

Staff: On Being is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Casper ter Kuile, Angie Thurston, Sue Phillips, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Damon Lee, and Jeffrey Bissoy.

Ms. Tippett: Special thanks this week to Tom West and Tom Mudge.

Here's the transcript:

Krista Tippett, host: This hour, an exuberant experience of conversation and singing the spirituals. There are nearly 5,000 spirituals in existence. Their organizing concept is not the melody of Europe, but the rhythm of Africa. They were composed by slaves, bards whose names we will never know, and yet gave rise to gospel, jazz, blues and hip-hop. Joe Carter lived and breathed the universal appeal and the hidden stories, meanings, and hope in what were originally called “sorrow songs.”

Joe Carter: What we're talking about is human suffering, and how do we survive when the worst happens? What are the mechanisms? I can sing "Motherless Child" in Siberia; they know what it means. They've been through hell. I can go to Scotland and Ireland and Wales and sing these. They understand the sentiment. The songs have become symbolic, I think, of that universal quest for freedom, that yearning for freedom, and that part of us that says, "I will not be defeated."

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

This was one of our first weekly shows and it’s still one of our most beloved. Joe Carter remained relatively unknown through his death in June, 2006. But he performed for more than 25 years in opera and musical theater and he portrayed Paul Robeson in a one-man musical. I spoke with him in a music recording studio in 2003, with his pianist Tom West nearby for whenever Joe might feel called to burst into song.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me what you think of when I ask the question about how this music played a role in your earliest religious life, and what songs, or what song, comes into your mind first and why.

Mr. Carter: It takes me back to my childhood in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and my church, which was Union Baptist Church, the main black church in Cambridge at the time. We didn’t have spirituals in the church, and we didn’t have African-American gospel music. It was a period of time when there were a lot of African Americans who were saying, we’re not connecting to our history. We want to show everyone that we can be integrated. So we were singing European anthems, so I never heard it in my church except when there was a baptism. And when the preacher would go into the baptismal pool and he’d come out, he’d immediately begin to sing [singing] “Everybody sing amen, amen, hallelujah, amen, amen, amen.” There was no pipe organ, no piano, he was just singing a cappella and the church would begin to rock. And as a child I remember — wow, what is that? There’s something special about that song, about that music — and I was always excited when I got a chance to hear it, but I didn’t get to hear it very often in my church.

Another time I heard it was on recordings. We had an old scratchy — I think it was a 78 recording, and it was a choir called the Wings Over Jordan Choir, and they were an African-American radio choir in the early days. And it was something we didn’t hear very often. They were spirituals.

Whenever we played this record it was almost a total hush in the room, in the family, because it was the story of Mary McLeod Bethune, who was a relative of ours, and it tells the story of how this little girl was the first one born free in her family, how she wanted to learn to read and write, and in the background you’d hear the Wings Over Jordan Choir singing spirituals.

[music: “I Will Trust In The Lord” performed by the Wings Over Jordan Choir]

And somehow it was during those experiences I realized there was something very special about this music that was different than jazz, blues, and rock and roll that we played on the record player, or even some of the gospel songs. This was something that was even more powerful. And I think I had developed a real desire to learn about it.

Ms. Tippett: So tell me what years are we talking about — when were you born, when were you growing up?

Mr. Carter: I was born in 1949. So I was a child of the ’50s and the ’60s. And then the civil rights movement came along, and everyone was singing spirituals. And in Cambridge we had all the folk singers. And when I was 15 years old I got into a folk singing duo with my best friend at the time, with David Levithan who’s Jewish, and David told me, "Joe, your people have wonderful music." And this was the first time I'd ever heard someone say that. So he wanted to come to my church to hear the music. So he came to Union Baptist Church on a Sunday morning and heard Bach. He said, "Joe, that ain't it." [laughs]

And so I began to search for places that I could share this music with David and hear it myself. So we would go into the ghetto in Boston and we’d go around little store-front churches and we’d go, “This is it! This is it! You hear the tambourines beating and the people? Oh, yeah.” [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: Oh gosh, there’s so much I want to pursue here. First of all, it’s very intriguing to me that you started on that journey with a Jewish friend because I think so many of the stories that the spirituals captured came from the Hebrew Bible, the story of the exodus.

Mr. Carter: Absolutely, that's true. We had a folk-singing duo, David and I, called the Dithy Ramble Duo. And we sang “This Train Don’t Carry No Gamblers” and those songs that were popular in the ’60s. And that was kind of a beginning.

Ms. Tippett: Tell me what your family’s connection was with the world in which the spirituals were created, which was the world of black slavery.

Mr. Carter: I think it’s only as an adult I really began to understand that because my parents were very careful not to talk about their pains and the things that the ancestors went through because they didn’t want us to grow up with, so-called, a chip on our shoulders. They want us to be free and to realize that prejudice was an evil thing and we must not let it be found in us. But later I realized my grandparents were born right after slavery. So all of my great-grandparents were born slaves, my grandparents grew up on the plantation, my parents as children were on the plantation as share croppers and moved to the North mainly to flee the persecution of racism and brought us to a place that was an international community. And every once and a while I would hear my mother or my father singing a little song very quietly, they wouldn’t sing openly — or my grandparents. And I'd say, “What’s that song?” “Oh nothing, nothing, nothing.”

Ms. Tippett: Do you think that these were songs that they really carried around inside them. They weren’t consciously humming them.

Mr. Carter: Yeah they did. I think they heard them from their parents and their grandparents and they were just songs that they sang for comfort.

Ms. Tippett: So I think — and it was only as I prepared to speak with you — that we celebrate this music now, right? American culture as a whole celebrates this music. We don’t think very hard or very often about where they came from and how that is speaking to us also through this music. And it was also — this question that James Weldon Johnson raises in the book that you gave me from 1925, the book of spirituals, about who wrote this music — that there must have been bards, that there were great artists at work. Is there folklore around that that came down to you through your family? Is there a memory of that? What do you think, or what have you learned?

Mr. Carter: Well, I discovered a few things as a teenager. I met a woman by the name of Jessie Anthony who was — I think she was over 80 when I met her. And somehow, she was coming to our church. And we young people would go to her house to collect her, to bring her to church and so on. Well, here was an African-American woman whose parents were slaves in Virginia. And she sang the spirituals. And she'd heard me sing in church, so she just sort of took me under her wing. And she was going to teach me these songs. And she had a suitcase full of stories that she'd collected over the years of the spirituals. And she would tell me, she'd say, “Child, when they sang this song, this is what they were talking about, you know? A lot of people don't know this.” And she had stories for every song.

Ms. Tippett: OK, tell me a story.

Mr. Carter: One of the stories I seem to remember that she told, it was about — Emancipation Day had come. There was a group of former slaves, now, on an island off the coast of South Carolina. My parents were from South Carolina, all my family. And they were waiting for the emissary of the government to arrive in his little boat to tell them that they had received the deeds to their land, because the government had promised them not only freedom, but 40 acres and a mule. This was going to be a great, wonderful day.

And the former slaves had gathered together on the island waiting with bated breath. And finally, they saw the boat of the officer approaching. And they could tell, even from the distance, that his face was not happy and his countenance was somewhat sad. And they said there was a groan that just came from the crowd. And one of the older women from the crowd just stood up and began to make up a song on the spot. Do you want me to show you what that song is?

Ms. Tippett: Yeah, I do.

Mr. Carter: I’ll go to the piano. She sang,

[singing] Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows but Jesus

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory, hallelujah

And then she spoke, looking to the people around her, she said,

Sometimes I’m up, sometimes I’m down

Oh, yes, Lord

Sometimes I’m almost level to the ground

Oh, yes, Lord

Oh, nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Nobody knows but Jesus

Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen

Glory, hallelujah

Ms. Tippett: And sorrow songs, is that what the spirituals were called routinely?

Mr. Carter: Yeah, that's what I'm told.

Ms. Tippett: And it does connote — it connotes what's in the music, but it connotes something different from the title "spiritual."

Mr. Carter: Mm-hmm. Because they were the expression of the great pain and the sorrow. But at the same time, they were always looking upward. They were always reaching. There was always some level of hope, as opposed to the concept of the blues. The blues was just singing about your troubles, and there was no hope. But there's always the glory hallelujah someplace saying, "Oh, and on that glory hallelujah, then we fly." So in the midst of the night, we can fly away to freedom while we're singing these songs. And this is another.

[singing] I am a poor pilgrim of sorrow

Down in this wide world alone

No hope have I for tomorrow

I've started to make heaven my home.

Sometimes I'm tossed and driven, Lord

Sometimes I don't know where to roam

I've heard of a city called heaven

I've started to make heaven my home